Chris Jojo - Senior Sound Designer, Codemasters

Sennheiser’s Pro Talk Series on YouTube features interviews with the industry’s most respected audio professionals, including Chris Jojo, senior sound designer and principal sound recording engineer at Codemasters Studios in Southam, UK.

With a “Racing Ahead” tagline that pays homage to the video game format that grew the company into the powerhouse it is today, Codemasters’ biggest titles include GRID, Formula One and DiRT (DiRT and DiRT Rally) series racing sports games.

Codemaster was founded by brothers David and Richard Darling in 1986. “They developed a series of titles that gained a lot of popularity in the marketplace and established themselves as award-winning developers of motor sports titles and adventure games,” explains Jojo. “They were subsequently bought out, but the Codemasters brand was retained and still continues with motor sports titles and racing simulations.”

Jojo himself has also long been in the gaming industry, having gotten his start in 1992 - shortly after the Codemasters name hit the market. “Over the years, I'd worked for a few British-based publishers and, in the early 2000s, I started freelancing on game audio and writing and producing music for TV and commercials. [At that time, a] colleague working at Codemasters offered me some freelance work. I'd had working experience with him in the past, and that kind of spilled over. He was trying to sort of coerce me into committing to work in a studio environment full-time. I came on board in 2009 to work on DiRT 3, and I've been here ever since.”

Prior to going full-time with Codemasters, Jojo was involved with a lot of bands and was working in Hong Kong for a post-production house. “One of my friends [was] working in the QA department for an emerging game software developer based in Manchester,” he says. “He asked me if I would be interested in writing music and doing art and illustration for what was then the early eight-bit console -- Nintendo and Sega consoles. I came back from Hong Kong [for] a little bit of a breather and I took him up on his offer. I basically just chilled out there and they offered me a job to write and program music and sound for games.”

Shortly thereafter, that group of professionals became part of the Nintendo Dream Team, a very exclusive and limited number of developers exclusively hired for Nintendo. “We had some very talented programmers there who managed to create their own [development] tools and Nintendo got wind of that, [so] we became part of that click of developers,” adds Jojo. As a result, “I cut my teeth on very early sample-driven and sound chip-driven eight-bit and 16-bit console stuff. Back in the day, you basically had to crank out the music, sound design, speech, whatever it was, from memory. Going back from the 90s to where we are now, it's just staggering how things have evolved to where we are now. The development cycle back then could have been six months or even less. Now, we're looking at a year to two years, depending on the size and the scope of the game. And, where it may have been a handful of sound, designers, [now] we’re looking at a phalanx of sound designers and people specializing in a technical integration and creative sound design.”

In modern game design, Jojo explains that there are people assigned as the leads or architects for each area, including game audio. “It's quite impressive how far things have come,” he continues. “The area that we're involved with is firmly rooted in reality, obviously, being sim based. So, we're kind of charged with trying to convey that element of realism using the most authentic assets that we can source and trying to create assets that we can implement into the build. They are as realistic and as dynamic as possible.”

Within the audio department at Codemasters, there are teams assigned to specific projects, including those currently in development -- including Jojo and his colleague David Sullivan, who are primarily involved with engine sound. “I deal with a lot of capturing assets that are going to be useful to anything specific that we need, and David is responsible for building the engine audio. We have an F1 (Formula 1) team as well, who work exclusively on that. The idea is that amongst the designers are senior level and maybe some junior level designers dealing with a specific set of audio systems. So, someone might be focusing purely on ambience, spot effects, UI, adaptive music or speech. Across all those areas, [the designers] bear the responsibility of creating and integrating those assets and liaising with the audio leads. They're the grand architects of each of those projects, so they oversee what everyone's doing. It's a position of very high responsibility and quite a high-pressure role. Not to detract from the other work that people are doing, but that they're essentially keeping the hand on the tiller while we're just cracking on.”

With modern game audio, regardless of the format, developers aim to impart content that's desirable for the end user and ensuring engagement with the market to increase the longevity of a title or series. “We're kind of fostering a sense of community around a project itself,” adds Jojo. “We have a lot of drivers and motorsports enthusiasts who play Codemasters titles, so you've got to make sure what you're doing is as authentic as possible. I've been working on DiRT Rally 2 and another title being developed that’s gonna be released in 2019, [which] necessitates me being focused primarily on sourcing and recording cars because of the sheer size of the content. There's a kind of pooling of our audio staff in some instances. One designer can share assets across another project, so it gets very fluid.”

Among the main pieces of audio that Jojo is tasked with capturing is audio from within the cabins of as many different shells -- such as rally or touring cars -- as possible. “I was looking at sound field mics as a tool for capturing 360-degree audio to pull in everything within an environment or even for Foley design,” he explains. “It's a great way to record props or car parts, anything externally in an outside location that would be representative within a rally stage or on track. You're capturing a subject that's breathing in its own environment, so when you drop those assets into the game, you don't have to worry too much about processing. Within the environment, it sounds a lot more natural. Recording something very starchy, anodyne and bland in a foley studio with a dry mic is not realistic enough. My approach is to record within an ambient environment, but have nearfield close-mic’ing to capture the punch of the transience. There are just so many areas of our systems that can employ ambient recordings. We're kind of future-proofing our library and an archive with the [Sennheiser] AMBEO VR Mic. For the better part of seven months, I've been using that [for all the] on-board sound recording sessions that I've done for DiRT.”

For many of the projects on which Codemasters is involved, the venues have a gravel tarmac, which causes particulate to get up into the underside of a vehicle as it races down the course. “It's a very high frequency sound, but stuff like that that might be just incidental to what you're doing on an on-track recording session,” says Jojo. “A lot of circuits have very large jumps. So the sound of a car bottoming out, it's a very specific sound; it's like the skimming kind of (crunch).”

Jojo goes on to explain that there’s a method to the madness behind capturing true sounds for a video game. “We were thinking about object-based audio -- it's always the 7.1 or ambience that's the high-end ordering of the playback format we're looking at,” he says. “Everything can be folded down to that but, within that matrix, we can preserve the higher order ambisonic inserts in the signal. In a rally car, you're going through so many different types of landscapes and environments. We had a field recording trip and we just recorded trees, bird songs, rivers, lakes, streams, anything like that. I've used AMBEO VR Mic for quite a few of those things as well.”

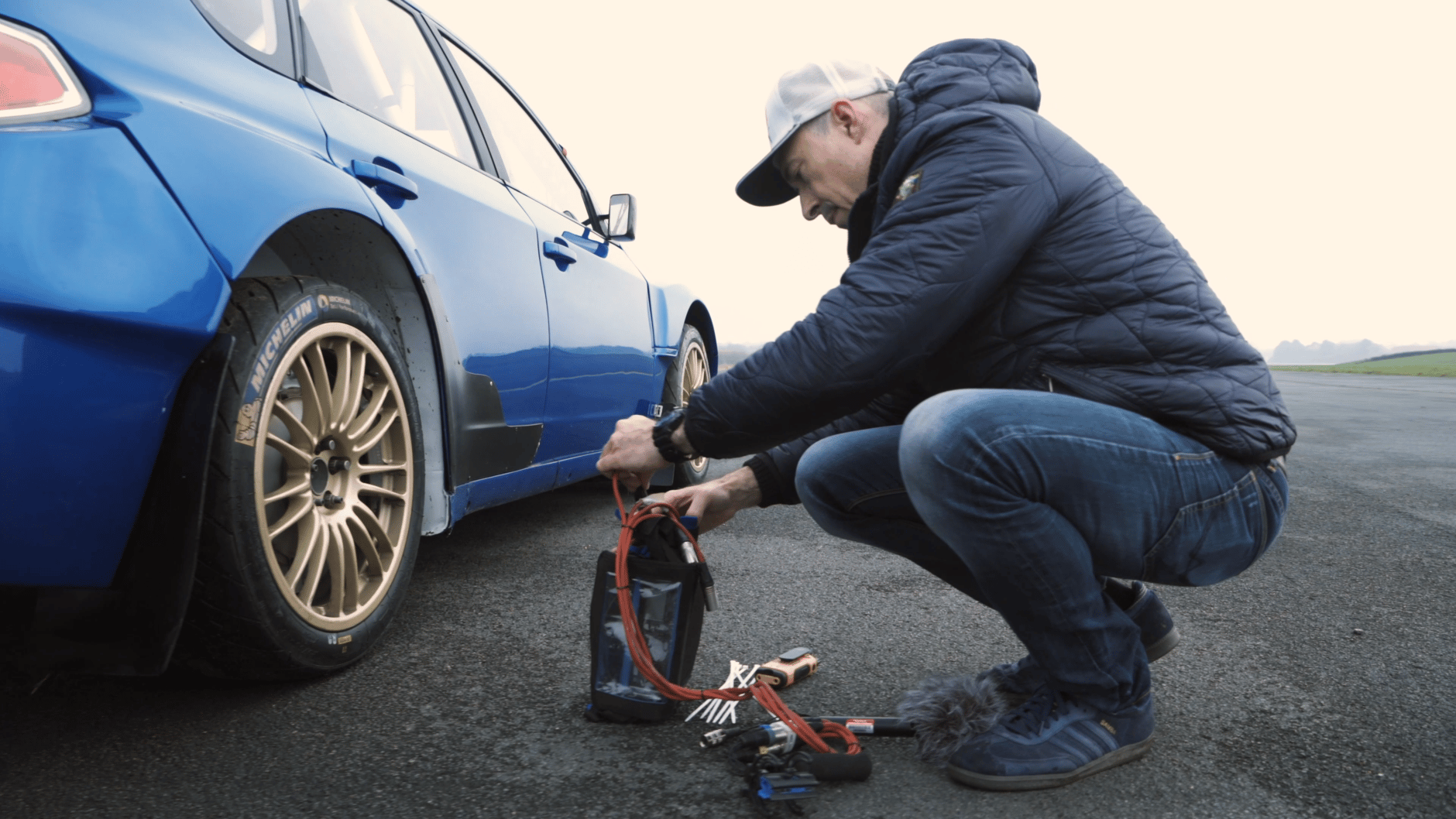

Among the many things that Jojo has recently been tasked with recording was the subguard from a Tommy Macken Mitsubishi Lancer Evo 6, on loan from SVP Motorsports. “We recorded that with theAMBEO VR Mic and a DPA 4011 just to capture the transient and a little bit of bite,” he adds. “That's where the AMBEO VR Mic helps; it's just a really useful tool. For crowds in stadiums with the smaller bleachers that you get in in rallycross events, [the AMBEO VR Mic is] perfect. To sit in the midst of that and just hear the rise and fall and swells from those crowds is great.”

In other instances, Jojo will record the day-to-day happenings of a racing event - such as teams welding pieces of the cars or replacing tires in a heat, the announcements over the PA or a blimp flying overhead. “To be able to jump into the midst of that before the AMBEO VR Mic, it was more of a case of recording stereo within an environment,” he says. “It's good to have more spatial recordings and more breadth in terms of the 360-degree dimension; I want it to be as immersive as possible. I just think [the AMBEO VR Mic is] a fantastic tool for capturing a breadth and scope of audio, so we don't need multi mics. You have that in your backpack and maybe a little shotgun depending on what it is you're recording. Roving around, I just have those two on the fly and just bring back the goods.”

As the AMBEO VR Mic is largely intended for the VR space, it lends itself well to future-proofing the content that Codemasters is capturing. “The ambisonic [sound] within the 7.1 environment can be preserved to output, so further down the line, if they decide to convert to VR, there are plugins now to create a VR mix. In periscopic audio, those are the dimensions that you want. If you're in a combat game or you've got a hail bomb flying over your head, that's just going to throw you into the scene. You can be totally immersed and it's going to get the adrenaline rushing. To have that in a rally car -- if it's kick up, or detonations, something backfiring or sputter of overrun -- assets recorded in the cabin space, just lend itself to that. [When] I place the AMBEO VR Mic at a rallycross or touring car event, we are capturing that in three engines in a spherical surround, ambisonic format. It's far more desirable than just trying to hack it or credit with stuff that you recorded.”

Regardless of the final video output, capturing the authentic sounds of racing events is a top-priority for the Codemasters teams. “We'll have seats with manufacturers, [car owners] or [racing] teams and they tell us what they like about the game,” explains Jojo. “And it's not just limited to how the car's handling and operating in the game, they're actually picking up on sound. With the loadout for a given car, I'll know what I'm recording; I'll look at the engine and exhaust, I'll check the specs and then that will determine what I'm going to bring to the session. So, capturing that and nailing it and putting that in context which then exhibits a specific sound -- there's nothing like it.”

Jojo continually strives to capture the “sweet spot,” which is “as close to the driver's position as possible, but also I want to make sure that I'm picking up the transmission line wherever that might be. From about 30-odd recordings we've done so far in inside of the year, [the AMBEO VR Mic has] just been consistently good, I haven’t had to worry about it. One of my concerns was the sheer power of some of these cars internally, they are incredibly noisy. I haven't had to put any inline attenuates [on the comms], but on the engine's exhaust recordings, I use 20 dB pads. I've been upping it to 40 dB now because a lot of the cars I'm doing for this unannounced title are incredibly loud. [The AMBEO VR Mic is] a powerful tool because you're pulling everything within a 360-degree environment. There are a lot of factors that influence where you're going to put the microphones [and] what microphones you're going to choose. You might want a focused super-cardioid or something that can handle high transients, so that it's got that SPL handling. The criteria for selecting mics: clarity of reproduction, weatherproofing, bespoke enclosures to protect them from wind and heat, [etc.].”

In approaching mic’ing up a car, the Codemasters team is focused on capturing everything within the engine bay and exhaust using several different types of cameras that they use both within the games and as reference points. “In order to disambiguate those, [we use] impulse response on the elevated mics [in the cabin]. For the exhaust, it depends on the engine configuration and [induction type, such as] if it's forced induction or twin turbos, if it's got waste gates or if it's normally aspirated. We want to capture the engine, but we also need to isolate those facets. You've got to basically apply a discrete mic’ing approaching where you need to disambiguate so you can mix to taste or you can omit one from the actual overall mix. The other important consideration is air flow, heat and the amount of room that you have available. Wind buffeting is obviously the enemy of all exhausts. My mainstay is the [DPA] 4007, which is the foundation. To capture bite or get a bit of detail on the exhaust, I use the Sennheiser MD 421-II for dynamics; the [Sennheiser MKE] 440 is good as well. We still have lavalier mics, but I'm trying to move away from some of the live connectors.”

Another consideration for Jojo, and the entire Codemasters team, is the end-user of the games they are producing - with regards to what gear they are using to play. “I think headphones is probably what a lot of kids and teenagers are gonna crank on and play a game through, but I think most people are playing through stereo televisions or they might have a soundbar,” he says. “The 20-somethings with money to burn, or the or the guys who've got the vanity theatre, [will play] with 7.1. That's the best way to play the game, but not everyone has access to that or not everyone can really play at that level. The more authentic [and] all-encompassing you can be with pulling in that content and adding the detail, depth and nuance means we've got a bigger canvas to work with; and that works across the board for graphics [and] VFX. If we do our job right, then across all those formats and platforms, we've got a mix that would sound balanced and would inform the player as well. If you forget about the tech you’re just there - then we've done our job.”

For Jojo, these accomplishments are the highlight of his career. To have “the opportunity to get out there and into environments that are interesting and layered, or if you're enveloped in sound sources [that are] aurally interesting, those are the recordings you're going to look back on. It's like a writer writes, the recordist records. Think, ‘wow, oh yeah I want to be on [that]; I want to use that; I want to put that to use.’ Just look for interesting opportunities; seize it when you hear it. There's always something you're looking out for, and you don't know until you're there. I think most sound designers are like that.”